If you haven’t read last week’s post, I suggest that you go back and read it before continuing on. But, as a brief refresher, last week we looked at the Cosmovitral, designed by Mexican artist Leopoldo Flores, and tried to see what philosophical/theological conclusions we could draw from that. From looking at his panel “Birth,” I proposed that we could take two philosophical conclusions from this:

- The universe is seen by the artist as emerging from something.

- That from which the universe emerges is somehow related to an act between two beings.

From there, I suggested that, if the universe emerges from something, then we must ask two questions: from what does the universe emerge? And, what is our relationship to this origin? Christian belief proposes that God is that from which the universe emerges. We’ll explore our relationship to God in this post.

After this, I argued that Flores is trying to show that there is an action that is at the core of all things within the material universe, from the smallest subatomic particle all the way up through mankind. Following Fr. Pierre Teilhard de Chardin SJ, I argue that love is the most basic principle of Being Itself. From this, we see that the universe is evolving towards Love (that is, towards God), and then I proposed that this is the reason why God must be a Trinity: love requires both a lover and a beloved.

Today, I want to move beyond these philosophical/theological ideas and move into the realm of spirituality. As such, we’ll look at two questions: what is our relation to our origin? And what does all this business about love as a principle of Being Itself mean for our lives? For both of these questions, I will draw heavily upon Pope Francis’ recent encyclical letter, Laudato Si’: On Care for Our Common Home.

We’re Creatures; not the Creator

So, if we assume that the universe emerged from something, and we want to inquire as to our relation to the origin of the universe, this seems like a daunting task. Indeed, I think it’s a question that has left many people earnestly seeking God in the dark for a long time. But the question gets a lot easier if start with one obvious fact: if the universe emerges from something, and we are part of the universe, then we emerged from something. As such, we are not the origin of the universe. In short, we’re not God. Let’s consider this passage from Paul:

“He [Christ] is the image of the invisible God, the first-born of all creation; for in him all things were created, in heaven and on earth, visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or principalities or authorities — all things were created through him and for him. He is before all things, and in him all things hold together. He is the head of the body, the Church; he is the beginning, the first-born from the dead, that in everything he might be pre-eminent. For in him all the fullness of God was pleased to dwell, and through him to reconcile to himself all things, whether on earth or in heaven, making peace by the blood of his cross.” — Colossians 1:15-19

Leaving aside for the time being the question that this passage seems to raise about the divinity of Christ, let’s examine this passage a little more closely.

Love as the Principle of Being Itself

Last week, we looked at Teilhard de Chardin and the idea that love, that is, the desire of all things to unite into a larger whole, is at the basis of all created things. To me, the aforementioned passage from Paul seems to confirm this idea. Paul tells us that “in him, all things were created.” While I am not a Biblical scholar, it seems like we could take this to mean that, in the love of the Father for the Son, all of the universe is created. We are born from the love of the Father for the Son, and created by the Father for the Son (“all things were created through him and for him”). As such, it is in Christ alone that we find our purpose (“and in him all things hold together”). Furthermore, not only is he the head of the Church, the body of believers, but ALL THINGS are held together in him. As such, if we adopt Teilhard’s view that we are all journeying towards a moment when all creation will look upon the face of God unveiled, Christ is that point. To use Teilhard’s language, Christ is the “Omega-Point” of our universe (if you’re tempted to think about this as pantheism, please see my explanation of why this cannot be seen as a pantheistic whole in Part I).

In summary, Paul gives us, with the passage from Colossians, some really important principles of our relationship with our creator:

- We were created in the love of the Father for the Son.

- We were created for (read: as a gift to) the Son*.

- In Christ alone we find the purpose for our lives.

- Together with all of Creation, we are held together in Christ; he is our beginning and our end, and we are only truly ourselves when, alongside all of Creation, we are united with Him.

- Through Christ, the broken relationships between us and God, between each other, and between ourselves and the rest of creation are reconciled.

* One of the great joys of the religious life is the daily nourishment of the Psalms, which we pray 5 times/day. This point reminds me of a line from one of my favorite Psalms (Psalm 104): “There is the sea, vast and wide, with its moving swarms past counting, living things great and small. The ships are moving there and the monsters you made to play with.” For me, it’s a reminder of God’s omnipotence: even the most powerful, scariest, largest creatures are ultimately made so subordinate to God that they are his play-things…

Pope Francis and the Gospel of Creation

One of the most awesome things I’ve read in a long time is “The Gospel of Creation,” the second chapter in Pope Francis’s encyclical, Laudato Si’. I think that the five points of relation that we mentioned between ourselves and our origin in the previous section can be summarized well by Pope Francis’s words:

“…human life is grounded in three fundamental and closely intertwined relationships: with God, with our neighbor and with the earth itself. According to the Bible, these three vital relationships have been broken, both outwardly and within us. The rupture is sin. The harmony between the Creator, humanity and creation as a whole was disrupted by our presuming to take the place of God and refusing to acknowledge our creaturely limitations.”

In short, we’re not God. And as such, a well-lived human life is one that acknowledges this and lives accordingly, in harmony with God, our fellow human beings, and with all of creation. To do this, our spirituality (and spiritual lives) need the following parts: Praise, Thanksgiving, and Communion.

Praise

“Nature is usually seen as a system which can be studied, understood and controlled, whereas creation can only be understood as a gift from the outstretched hand of the Father of all and as a reality illuminated by the love which calls us together into universal communion.”

“When we can see God reflected in all that exists, our hearts are moved to praise the Lord for all his creatures and to worship him in union with him.”

The above excerpts from Laudato Si’ touch upon what I think are the most important components of a Christian spirituality. We are made to praise God; we are made for Him. And, indeed, all of Creation is made to praise God. But authentic praise can only arise our of a spirituality that is aware of the grace of God, that sees the face of God in all things. This is an attitude that we ought to ask God for, and it is an attitude we ought to try and cultivate. I’m convinced that we have to do this by developing a spirit of thanksgiving.

Thanksgiving

What happened in the last five minutes that you’re grateful for? For me, this isn’t an easy question. I want to lean on the usual stuff: family, friends, music, the consolations of God, my life…

But what if I narrow the spectrum? What if I was alone, working all day? What if God feels really distant? What if I’m sick and feeling like crap? What did God give me today for which I’m grateful? This is a hard question. But if we really believe in God, every day is a re-creation of the first day; every day is a new beginning, a moment of intimate communion with God that never was before and never will be again.

One of my favorite bloggers, Scott Alexander, wrote this post. Even though he’s an atheist, I think he touched on a very important spiritual truth (though I’m sure he interprets it very differently than I do): “Once the pattern-matching faculty is way way way overactive, it (spuriously) hallucinates a top-down abstract pattern in the whole universe. This is the experience that mystics describe as “everything is connected” or “all is one”, or “everything makes sense” or “everything in the universe is good and there for a purpose”. The discovery of a beautiful all-encompassing pattern in the universe is understandably associated with “seeing God”.

The key here is that the great Chritian mystics, those that are intimately connected with God, are those that are aware of His presence in every moments. In non-spiritual terms, those who make use of their pattern-matching faculty. So, if we want to cultivate a life of praise, where we are praising God with all of Creation for all time, then we need to cultivate an awareness of the presence of God. For me, I find that the easiest way is to figure out what I’m thankful for in any given moment, then I’ve found the presence of God.

We take on faith that God exists and gives us this moment. From there, we move to seek His presence.

Communion

Lastly, we need communion. I remember a friend of mine was once dismayed about a mutual friend of ours who wasn’t Christian. He said to me, “I just can’t imagine it would be all that great to share in the beauty of God without [friend’s name].” And, he’s right. I love a lot of people really deeply. And if you asked me if I wanted to be united to God without them…if I said yes at all, it would be only after a very long struggle. Luckily though, we don’t have to. Somewhere along the way, Protestantism got this idea that everything was about a “personal relationship with God.” Don’t get me wrong, that’s an important part, but equally important is our communion with each other and with all creation.

“God wills the interdependence of creatures. The sun and the moon, the cedar and the little flower, the eagle and the sparrow: the spectacle of their countless diversities and inequalities tells us that no creature is self-sufficient. Creatures exist only in dependence on each other, to complete each other, in the service of each other.” – Catechism of the Catholic Church, p. 340

We all, individually and together, belong to God. And as such, “Every creature is…the object of the tenderness of the Father, who gives it its place in the world. Even the fleeting life of the least of beings is the object of his love, and in its few seconds of existence, God enfolds it with his affection” (Laudato Si’, p. 77). We’re all connected, our actions make differences in each others’ lives, and we all have to love each other and take care of each other. We have to do so because we were all created to praise God, to worship him together. We were created as a Communion, and it is only because of sin that we lost this Communion (and continue to lose it). And the idea that we can praise God outside of this Communion of caring for each other and Creation is a lie; as Roland Rolheiser powerfully states: “You cannot deal with a perfect, all-loving, all-forgiving, all-understanding God in heaven, if you cannot deal with a less-than-perfect, less-than-forgiving, and less-than-understanding community here on earth. You cannot pretend to be dealing with an invisible God if you refuse to deal with a visible family” (The Holy Longing, p. 98). Like it or not, we’re bound together for eternity, so we damn well better figure out how to love each other and praise God together.

Consequences

The sub-title of Laudato Si’ is “On the Care of Our Common Home,” and I would be remiss if I talked only about cultivating attitudes within ourselves and never mentioned the actions that these attitudes necessitate. As Pope Francis points out:

“A sense of deep communion with the rest of nature cannot be real if our hearts lack tenderness, compassion and concern for our fellow human beings. It is clearly inconsistent to combat trafficking in endangered species while remaining completely indifferent to human trafficking, unconcerned about the poor, or undertaking to destroy another human being deemed unwanted…Everything is connected. Concern for the environment thus needs to be joined to a sincere love for our fellow human beings and an unwavering commitment to resolving the problems of society” (Laudato Si’ p. 91).

All of that, of course, is in addition to the environmental problems that Pope Francis points out: loss of biodiversity, loss of clean drinking water, a warming climate, and global poverty. And others that aren’t specifically mentioned: excessive violence in the world (and excessive gun violence in the U.S.), unjust war, abortion, capital punishment, violence that targets people by race or sexual orientation…

We have to cultivate an attitude: an attitude of awareness and gratefulness for the presence of God in every moment of our lives. That comes first. But from this attitude, there are actions that must follow: first, we have to honestly look at and repent of the evil of which we are guilty in our own lives. Secondly, we have to see the grave social sin that surrounds us. This should sadden us, but not cause us to lose hope and not cause us to lose joy, for, “where sin abounds, grace abounds all the more” (Romans 5:20). But it should make us ask: what can I do to help with these problems? Then we have to take the action we can and entrust the rest to God.

Eucharist

The greatest form of Communion that we have on earth is the presence of Jesus in the Eucharist. Whenever we receive, or even just visit the Blessed Sacrament, Jesus is there. And in him is the “Omega-Point” that we talked about earlier; in him, we find our true selves, and in him we worship him in communion with the whole Church — and, indeed, with all of Creation. But, just as God is beginning and end, so too is the Eucharist a beginning and an end. It is the end because it is the most perfect form of praise, thanksgiving, and communion with God; but it is the beginning because it commits us to change our attitude and to change our actions. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church says:

“The Eucharist commits us to the poor. To receive in truth the Body and Blood of Christ given up for us, we must recognize Christ in his poorest, his brethren: ‘You have tasted the Blood of the Lord, yet you do not recognize your brother…You dishonor this table when you do not judge worthy of sharing your food with someone judged worthy to take part in this meal…God freed you from your sins, but you have not become more merciful.” – CCC 1397

One Last Thing (last one, I promise)

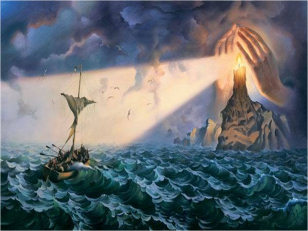

If you’re wondering how I got all the way here from the Leopoldo Flores exhibit, I leave you with two things: a picture and the ending of a short-story by Flannery O’Connor. The rest is up to you to figure out.

“The chapel smelled of incense. It was light green and gold, a series of springing arches that ended with the one over the altar where the priest was kneeling in front of the monstrance, bowed low. A small boy in a surplice was standing beside him, swinging the censer. The child knelt down between her mother and the nun and they were well into the ‘Tantum Ergo’ before her ugly thoughts stopped and she began to realize that she was in the presence of God. Hep me not to be so mean, she began mechanically. Hep me not to give her so much sass. Hep me not to talk like I do. Her mind began to get quiet and then empty but when the priest raised the monstrance with the Host shining ivory-colored in the center of it, she was thinking of the tent at the fair that had the freak in it….On the way home…the child’s round face was lost in thought. Her mother turned it toward the window and looked out over a stretch of pasture land that rose and fell with a gathering greenness until it touched the dark woods. The sun was a huge red ball like an elevated Host drenched in blood and when it sank out of sight, it left a line in the sky like a red clay road hanging over the trees.” – Flannery O’Connor, “Temple of the Holy Ghost”